A COMPLETE UNKNOWN - Review

The movies are magic sometimes, despite their imperfections

I’m no Dylan scholar, but I do love his music. When I first heard that Timothee Chalamet was to start in a Bob Dylan biopic called A Complete Unknown, I was intrigued - but skeptical.

My skepticism stemmed primarily from my knowledge of the industry market realities that led to this movie being made.

Market Condition 1:

Bohemian Rhapsody (2018) comes out. It’s one of the most despicable movies of the last 20 years, a moralizing karaoke machine that cheapens and tragicizes Freddy Mercury’s brilliant comet of a career arc. It was also directed by an absentee rapist, and its abortive final edit somehow led to an Oscar for film editing. It also won an Oscar for Rami Malek in the lead role, who did, admittedly, try very hard. Oh, and it made nearly a billion dollars at the box office, 20xing the production budget.

Market Condition 2:

Rocketman (2019) comes out, depicting the life of Elton John. This movie is too mediocre to complain about. It makes around $200 million against a $40 million budget.

So you have two classic rock biopics in a brief span. One is a industry-altering, exec career-minting box office monster. And the other returns a comfortable profit on a $40 million budget - something Hollywood has otherwise completely forgotten how to do. Calls are being made to music labels, and agents of legacy rock acts are starting to wonder when they’ll get their movie.

It’s not like musical biopics were some brand new thing - but Hollywood loves rediscovering old tricks, especially profitable tricks. So I didn’t expect much out of this movie. It seemed like a cash grab.

review

good things about the movie

Mangold does something very smart with his biopic, managing to evade the hacky conventions of the genre by speeding right past them. The movie mostly eschews plot structure, instead stringing us along from Big Moment to Big Moment at blinding speed, nearly a 2.5 hour montage.

We start with a precocious, anxious Dylan tracking down an ailing Woody Guthrie at his New Jersey hospital, where Dylan plays “A Song For Woody” to the impressed shock of Guthrie and Pete Seeger. Dylan ends up staying at Seeger’s that night; the next morning, Seeger overhears him composing “Girl From The North Country.”

We go like that, more or less, from Dylan's arrival in NYC all the way through going electric at Newport. We are carried at that speed through the whole movie, with the lightest daubs of plot to provide context for the musical moments. There are two major dramatic devices deployed: the first is a love triangle involving Dylan, his girlfriend Sylvie, and Joan Baez (played by the delightful newcomer Monica Barbaro). The second, which occupies most of the third act, involves Dylan going electric at Newport.

But the plot is almost besides the point in this movie. In fact, most of the other actors are besides the point. The reason you’ll go see this movie is Timothee Chalamet as Bob Dylan. For my money, it is the greatest performance of this kind that exists. You might prefer Seymour-Hoffman in CAPOTE, or Daniel Day-Lewis in LINCOLN; that’s fine. But this performance marks Chalamet as something approaching those prodigious talents, as one of our finest public artists, someone capable of far more than I knew.

Where a lesser actor would simply do a Dylan imitation, Chalamet inhabits a shifting, chimeric persona that spiritually channels multiple versions of Bob Dylan, and always feels entirely true. In an early scene, Joan Baez walks into a bar where he’s singing “Masters of War.” I gasped to myself in the theater, taken back as something uncanny happened to Chalamet, whose face seemed to morph as he sang. He was dissolving himself into this character, going somewhere normal people can’t go.

His guitar-playing and singing alone - Chalamet apparently has spent much of the last four years training for this role, and it shows - would set the film apart, and make it worthy viewing for any Dylan fan. Listen to his rendition of “Mr. Tambourine Man” to see what I mean.

As we move with Dylan through the stages of fame, Chalamet’s performance shapeshifts. At the start he is a prodigy who wants to prove it to everyone. He ages into something else, the image we all have in our heads, Dylan as icon: stooped shoulders, a sneer hovering above his teeth, his long arms hanging with a louche affect, or his model’s hands lighting a cigarette. Dylan, of course, was always playing Dylan, hyper-cognizant of his status as subject and object.

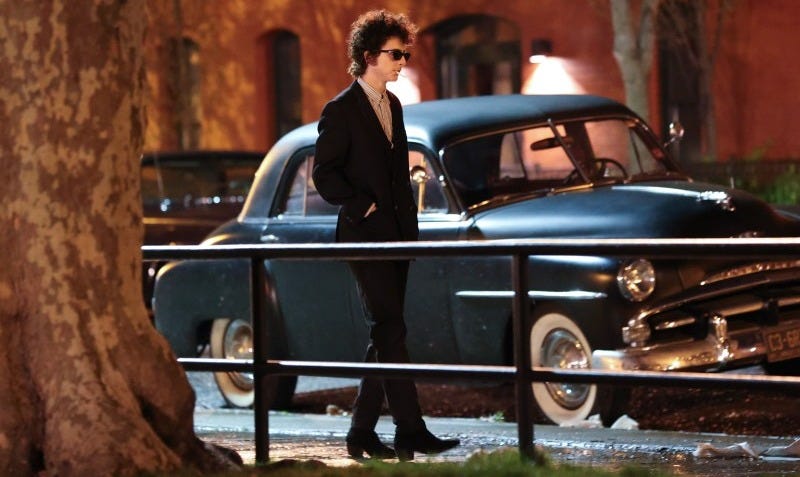

As Chalamet’s Dylan begins to feel the weight of hyperbolic fandom, as he is surrounded by yes-men, he withdraws into long hair in sunglasses. He becomes distant, mordant, strung-out and stoned at the same time. He becomes a total prick, too, but exudes a sexual charisma and effortless cool that overpowers any sort of negativity.

bad things about the movie

The downside of a scene-stealing performance like Chalamet’s is that it sucks the air out of a film, and makes the other characters feel shallow by comparison. Ed Norton is fine as Pete Seeger, but he plays it one-note. That may be how it was written, but it remains true. Elle Fanning is even less memorable as Sylvie, Dylan’s first girlfriend. Her role in the plot is to be less hot and less talented than Joan Baez. Tough beat for Elle, who seems like she has good taste.

Boyd Holbrook is interesting here. He has gotten a lot of buzz for how he plays Johnny Cash, which is strikingly different than director James Mangold’s last Cash, Joaquin Phoenix in Walk The Line.

While Phoenix crafted a moody, drug-addled Man In Black, Holbrook goes very big and very loud. He's got a gorgeous jawline and a helluva accent to match his rambunctious approach to the role, but it feels gauche in comparison to Chalamet’s subtle, blended work in the film.

Further confusing the role (which occupies no more than 5-7 total minutes of screentime) is Holbrook’s decision to play Cash as a swaggering, homoerotic flirt who appears to consider kissing Chalamet’s Dylan at one point. It's a little campy. Chalamet plays it very straight (literally), reflecting an ambiguous mirror to Holbrook's provocative acting. To be clear, it's not the idea of Johnny Cash as gay that bothers me. It's the guest-star energy, the feeling that he is trying to steal scenes - rather than act in them.

The aforementioned Monica Barbaro is the lone non-Chalamet standout as Joan Baez, although the movie’s breakneck pace doesn’t give her much room to explore the character. Her voice is tremendous, and she underplays her emotions in a way that suggests great intelligence and personal depth, making the most of her limited lines. She makes it easy to understand why Dylan fell for Baez.

overall

Mangold smartly fleshes out the cast with minor character actors and unknowns, so that the spotlight doesn’t stray too far from its star. This is the type of movie that could be terribly damaged with stunt-casting - make Seth Rogen the music agent and Jamie Foxx the old blues musician, and you’ve got a one-way ticket to schlockville.

That is not to say this movie completely forgoes schlock, of course. In a James Bond movies you have gunfights on motorcycles, and in musical biopics you some cheesy bullshit. There are about five too many listener/onlooker reaction shots. The songs do the work on their own, and at a certain point you get bored of seeing yet another actor do the facial WOW in reaction to a great Dylan song.

A few of the plot mechanics are too conveniently thematic to play well onscreen. For example, the city freaking out during the Cuban Missile Crisis - Joan Baez can’t get a cab, she’s trying to leave town, but she hears someone playing - and she happens to walk in on Dylan, doing the aptly timed “Masters of War.”

Of course that performance- which I praised earlier - is stunning, transportive enough to let you soar right over the mechanical elements that brought you there. And not all of the connective tissue is bad. When Dylan gets seriously famous for the first time, Mangold communicates it with a simple, effective sequence: Dylan rushes out of a building, mobbed by screaming teen girls, and ducks into a black car.

As it whisks him away, the girls still screaming and hitting the window, we see a mysterious look cross the young musician’s face. It cycles through stress, shock, and ultimately a cat-like pleasure in the chaos of renown.

In this scene and the rest of A Complete Unknown, Chalamet fully inhabits a famously inscrutable person, and never tries to make him scrutable. That is the performance and the film's greatest strength: its awareness that its hypothetical task - to know Bob Dylan - is impossible. You can’t get inside Bob Dylan’s head, so why bother trying? Instead, Mangold and (especially) Chalamet give him to us as he was, as he is: brilliant, enigmatic, with an intellect matched only by his ego.