Building New Memories of Bill Fox

processing memory and history and meaning through the semi-triumphant return of a reclusive Cleveland-area folk musician

intro

Last week, I sat in a row of leather seats at Gate 62B in Terminal 6 at LAX, waiting to board a flight to Dallas with my wife. The airport was quiet, even for a Wednesday night after 11pm. But even in the relative stillness, there is always a restless, discomfiting energy at the airport. I suppose it’s the nature of a transitive or liminal space, somewhere you go to get somewhere else. Speaking of transitive—Dallas wasn’t our final destination. My wife and I were going to meet her parents, with whom we would then drive to Arkansas for a brief vacation.

My RLS was already kicking in, quadricep and calf muscles pre-cramping in anticipation of the Basic Economy seating arrangements on Spirit Airlines flight 2416. I bent down and squeezed at my left calf, hoping to quiet the ache. It didn’t help, so I gave up and slouched deeper in my chair.

After a few tired scrolls on Twitter, something caught my attention. A culture writer named Nate Rogers, sharing his new piece for Vulture about Bill Fox, a press-shy songwriter-genius. I clicked over to Spotify—was this guy worth my time? I learned quickly that he was. This is a long piece, so I’d like you to start with a taste of the music. It is so good.

My intrigue went up a level when I read the accompanying article, and learned that Bill Fox was from Cleveland, of all places.

some background on cleveland

I never expect mysterious artists to be from Cleveland, partially because I am from Cleveland (the surrounding suburbs, specifically). There is, it always seemed to me, an inherently generic quality to the city that is difficult to explain to outsiders. It is “Midwestern,” which is to say bland. There is no signature cuisine or musical genre. Its primary cultural landmark is the Rock ‘N Roll Hall of Fame, which largely exists to celebrate the musical achievements of people from other cities. This broad sense of meh is exacerbated by the city’s post-hoc, formerly great status. Even amid a recent economic resurgence, many of downtown Cleveland’s buildings remain abandoned, or half-used. Most residents define themselves by their sports team allegiances. There's Browns guys, Cavs guys, and a smattering of Guardians (nèe Indians) guys.

In the defense of Cleveland, it wasn’t always like this; wasn’t always hollowed out. At the start of the 20th century, the city’s presence along the Cuyahoga River and Lake Erie made it a heavy-manufacturing economic powerhouse, a blue collar stronghold that neared a million in population at its peak in the 1950s. But the increasingly globalized economy and deindustrialization of the American Midwest hit Cleveland hard. By the time the ‘70s came around, Cleveland was in heavy decline. Jobs disappeared, families fled, and businesses of all kinds shuttered. During the nation-wide recession in the early ‘80s, Cleveland’s unemployment rate was 15% higher than the national average.

the musical context

For two decades—the ‘70s and the ‘80s—Cleveland was, however, a place where interesting rock music happened. A proto-punk scene emerged, marked especially by the formation of the Rocket From The Tombs, the 1974-1975 group who would splinter into the avant-garage rock band Pere Ubu and the infamous punk band the Dead Boys. The latter experienced more fame, signing a record deal with Sire Records (more on them later) and terrorizing venues all over New York City. But Pere Ubu left a more influential mark on rock history, inspiring well-known bands like Joy Division, Sonic Youth, the Pixies to craft the corrosive energy of punk rock into a more complex, textured melodic approach.

The biggest band to come out of Cleveland rock music was Nine Inch Nails, started by Trent Reznor after moving to the city in the 1988 to work at Pi Keyboards. But I’m not here to talk about Trent Reznor. Instead I’d like to shift your focus to The Mice, the band founded in 1984 by brothers Tommy and Bill Fox.

the musical origins of bill fox

The Mice were a power pop band with Tommy on the drums, Bill playing guitar, Ken Hall on bass. Bill wrote and sang all of the songs, which stand out for their catchy hooks. Even though the Mice played brief, simple songs with energetic riffs and a hard driving beat, they were decidedly not a punk group. Their forebears were Big Star, the Beatles, and the Kinks.

Their best-known song, “Not Proud of the USA,” is very good—and it’s also a strong entry point to the mythology of Bill Fox. Bill’s dad was a proud right-wing veteran who lost a foot to a landmine in the Korean war. He attended an early Mice show where they played this song. Tommy remembers Bill staring his dad right in the eyes as he played lead guitar and sang the dark, political invective.

Dad, you say you're proud of the USA

You’re so proud of the USA

When it moves you in many ways

Dad, the blood of the Indian tribes

Was it spilled so we could have such lives?

Where we wave flags above their graves

This song is a signpost for the type of music Bill Fox would eventually make. Power pop is not, generally, protest music. The genre historically leans into schoolboy romanticism, like the quintessential power pop group Big Star’s “Thirteen:”

Won't you let me walk you home from school?

Won't you let me meet you at the pool?

Maybe Friday I can get tickets for the dance

And I'll take you, ooh-hoo

The Mice’s sped-up, mod-inflected power pop started to make waves outside of Cleveland, and as 1986 turned into 1987 they toured played other states in the Midwest and received an offer to embark on a tour that would take them across the country and then Europe. As for what happened next, the details aren’t entirely clear.

By some accounts, Bill Fox just never showed up to the airport the morning of their tour’s first leg. Or he did show up, but told his bandmates that he needed to grab a pack of cigarettes, and never came back. Everyone agrees on one thing: it was Bill who canceled the tour, Bill who killed the Mice. Tommy, his brother and closest friend, was left to deal with the fallout from his mysterious absence. The brothers didn't speak for two years.

the songwriter era begins

No one really knows, exactly, what Bill Fox has been precisely up to over the last 35 years. There are bits and pieces, scattered through the scant media coverage of his career. The impeccable longform reporting that Joe Hagan did for The Believer, published in 2007, is available here. But Fox wouldn’t meet with Hagan, or even give him a phone call, so the story has a “Frank Sinatra Has A Cold” vibe—the narrative is structured by the absence of its purported subject.

I don’t want to get too deep into the bad stuff, the darkness. You can read the Hagan story linked above if you want to to learn about that. Suffice it to say that times were hard on Bill, who suffered from some occasional and intense bouts with mental illness at the turn of the decade.

More importantly, Bill Fox kept writing songs after leaving the Mice in 1987. Without a backing band—and crucially, without the sped-up rhythms of his maestro drummer brother Tommy—he transitioned to a gentle folkier sound. After his dad died, Bill used some of the money left behind for a studio session with local music world operator Tim Rossiter. There he recorded the stunning “Man of War” in 1991, which wouldn’t be released until 2025.

Stone of the nation, pride of a mother

Brother to us all

Rises at orders, marches past borders

To kill with a call

And if shell by surprise, should tear out his eyes

Then the truth gets even brighter than the day

Then all the Schwartzkopf'd and Sherman'd

More bound and determined, to blow the poor darkness away

“Man of War” is deeply indebted to Bob Dylan; in fact, you could have convinced me that this was a Dylan cover, or an early ‘60s deep cut from his war-protest era. The harmonica and the subject matter and the verbosity is all Dylanesque. But the more I listen to the song, and the rest of Fox’s discography, the more I note the distinctly Bill Foxian elements to the song.

For one, Fox was and is a master of internal rhyme and alliteration. Despite being a folk songwriter, he has a talent for writing very tight verses, with exactingly chosen syllabic structures. “…if shell by surpise, should tear out his eyes” stands out to me especially.

Further, there’s a deeply personal element to the writing. Where a classic early Dylan track like “Masters of War,” is abstracted, universalized in a near-mystical mode of songwriting—peak Dylan was always channeling something—Bill Fox’s songs are, ultimately, about Bill Fox. “Man of War” is about a deeply troubled man who wishes that he were someone else. Even if that someone else were evil, he thinks, it might be worth it. See the chorus:

And I've wandered and strayed 'neath sunshine and shade

Feet pounding from mountain to shore

Long as I've been free

I've wished I could be

As surе as a man of war

At some point in the early ‘90s, Bill Fox discovered the magic of home recording via four-track cassette tapes. From 1994-1997 he is said to have recorded well over 100 songs, and in 1997 the aforementioned Rossiter helped him release Shelter From The Smoke.

The album is a genuine masterpiece, and in retrospect it was wildly out of place in the coolness-obsessed indie rock world of the mid-late 90s. This is music without pretense; these are plain-spoken pleas for worldly justice and inner peace. “Over And Away She Goes” straight-up sounds like a Beatles song, with its closest era-specific correlate to the Beatles-y folk rock that Elliott Smith was making on the West Coast.

The most beloved song on the album is “Sara Page.” This is not a Bill Fox favorite of mine, and its cult notoriety is owed in part to its delightfully lo-fi recording. As the song begins you can hear a TV playing in the background; it provides ambience and texture, making the listeners feel as if we were sitting on Bill Fox’s couch while the song was performed.

I prefer “Appalachian Death Sigh,” a wistful country song about love lost accented by complex, swift melodic changes and some finger-picking thrown in for good measure.

When comes the day that you will weep and you will cry to find the one who will set you free

Just think back to Ohio and the chains of love you surely put on me

And when summertime is over and the air is chilled and snow begins to fall

How will I ever be so clever as to claim I never searched for you at all

I don't think I am being hyperbolic when I say this rivals anything Tom Waits or John Prine ever wrote. How the fuck does it have only 3.8k views on YouTube?

Back in 1997, Rossiter worked the phones to build some excitement for Shelter From The Smoke, and even convinced Fox to do some shows across the country after influential ‘90s outlet College Music Journal covered the album, crowning Fox as an “important” artist. Less than a year later, Transit Byzantium—another outstanding project, featuring the aforementioned career highlight “My Baby Crying”—was released, and buzz continued to build.

In 1998, Tommy Fox’s new band, the Revelers, got signed to a small indie label out of NYC called spinART. The Revelers’ bassist gave spinART a copy of Shelter From The Smoke, and its CEO Joel Morowitz fell head-over-heels, signing Bill and prioritizing him over the Revelers. (I'd like to offer a quick, empathetic nod to Tommy Fox here, whose musical career has been complicated, if not outright thwarted, at every stage by his genius older brother.)

Morowitz, sensing a hidden gem on his hands, got the album in front of Seymour Stein, the iconic founder of Sire Records, a music industry rainmaker who discovered everyone from the Ramones to Madonna.

Stein was impressed, and bought Bill an Amtrak ticket to come and play for him in New York. As legend tells it, Bill blew everyone in the room away, playing and singing dozens of gorgeous, polemical songs for Stein while staring him right in the eyes. Stein told Morowitz to develop the third Bill Fox album on behalf of Sire, and Morowitz set about planning the studio recording of the project in New York City.

Suddenly it was really happening for Bill Fox, happening again. He had earned that vanishingly rare thing, the thing you just don’t get in the music industry: a second chance. A hot indie label planning his next album, under the auspices of a music industry hitmaker. Indie magazines providing breathless coverage of his purported genius. And the cherry on top: Fox was scheduled to headline the CMJ Music Festival in New York.

Unfortunately, history would once again repeat itself. Bill refused the help of studio musicians, recording the promised album alone in Kent (a small Ohio town). The label hated the results. He never showed up to the music festival, and stopped returning phone calls. For all intents and purposes, Bill Fox had once again disappeared.

present day bill fox

It’s 2025 now, and Bill Fox is back. Sort of. He gave an interview to Vulture, exchanged emails with Steven Hyden of UpRoxx, and released two albums in the span of one month. If you have followed me this far into the rabbit hole, you won’t be surprised to hear that the albums are outstanding. My favorite of the new songs, from Resonance, is “Meat Factory,” a withering six and a half minute narrative about the blue collar misery of working at the slaughterhouse.

You waddle in an inch of blood

Ain’t no dam can block this flood of the meat factory

All your early childhood hopes

Get mangled in the blades and spokes of the meat factory

Pray someday, an office bench

Will raise you from the smell and stench of the meat factory

Move on at a steady pace

Keep a smile on your face at the meat factory

This song, like so much else from the pen of Bill Fox, takes you back in time. It is shot through with the bluesy, mid-century political folkie sincerity emblematic of Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger. But it's just better, frankly, than the best of Seeger. It reminds me again of early Dylan, before he swallowed that scene whole and spit it out, coated in snide rockstar irony. (“Judas!”)

This type of song only works when its writer is operating at the highest possible level; thankfully, Bill Fox is an Everest-level songwriter, and his hard-driving lyrics are paired with a world-weary vocal approach that imbues the song with a sense of depth earned through experience that Bill Fox, really, doesn't have. He's never worked at a meat factory. Based on the scant reporting we have, he has worked on and off as a telemarketer for various companies and causes over the last few decades.

Perhaps this quotidian, blue-collar adjacent professional life gave him the insight needed. Perhaps the “meat factory” symbolizes telemarketing, or the music industry, or life writ large. Or perhaps—like John Prine penning the impeccable “Sam Stone”—he is simply an artist-savant of the highest order, capable of accessing and communicating remote perspectives through music.

When you listen to the new Bill Fox songs, something jumps out right away: they sound just like the old Bill Fox songs. In fact, these aren’t “new” songs at all. These are new releases of old songs, all recorded between 1990-2010. It isn’t clear if Bill Fox has recorded anything in the last 15 years. Does that matter? Should that matter?

time, memory, and “new” (old) songs

After discovering Bill Fox at the airport, his music was a constant accompaniment over the coming days. I hit shuffle and kept at least one earbud in for the next week, only removing it when my wife’s immensely generous patience would occasionally run thin.

We stayed in Mount Ida on our Arkansas trip, a tiny town with a population of 1,103 at last census. Mount Ida was chosen for its quartz crystal mines that welcome recreational diggers, but we also took the time to visit an “antique” store there called the Mount Ida Flea Market.

I say “antique” because this business, which appears to literally be the owner-hoarder’s house, is a worn-down structure whose rooms are stacked to the ceiling with random, rusted, and torn accoutrement of varying origin. Much of the stock was “antique” only in the sense that it was old. Some of it wasn’t even that old. There was a room dedicated entirely to vinyl and, for some reason, empty soda bottles.

At first I was turned off by the disorganized nature of the store, so unlike the heavily-curated, aesthetically manicured vintage shops that adorn the yuppie streets of Los Angeles. But as I ventured deeper into the store, guided by the soothing lo-fi trauma melodies of Bill Fox, my perspective shifted.

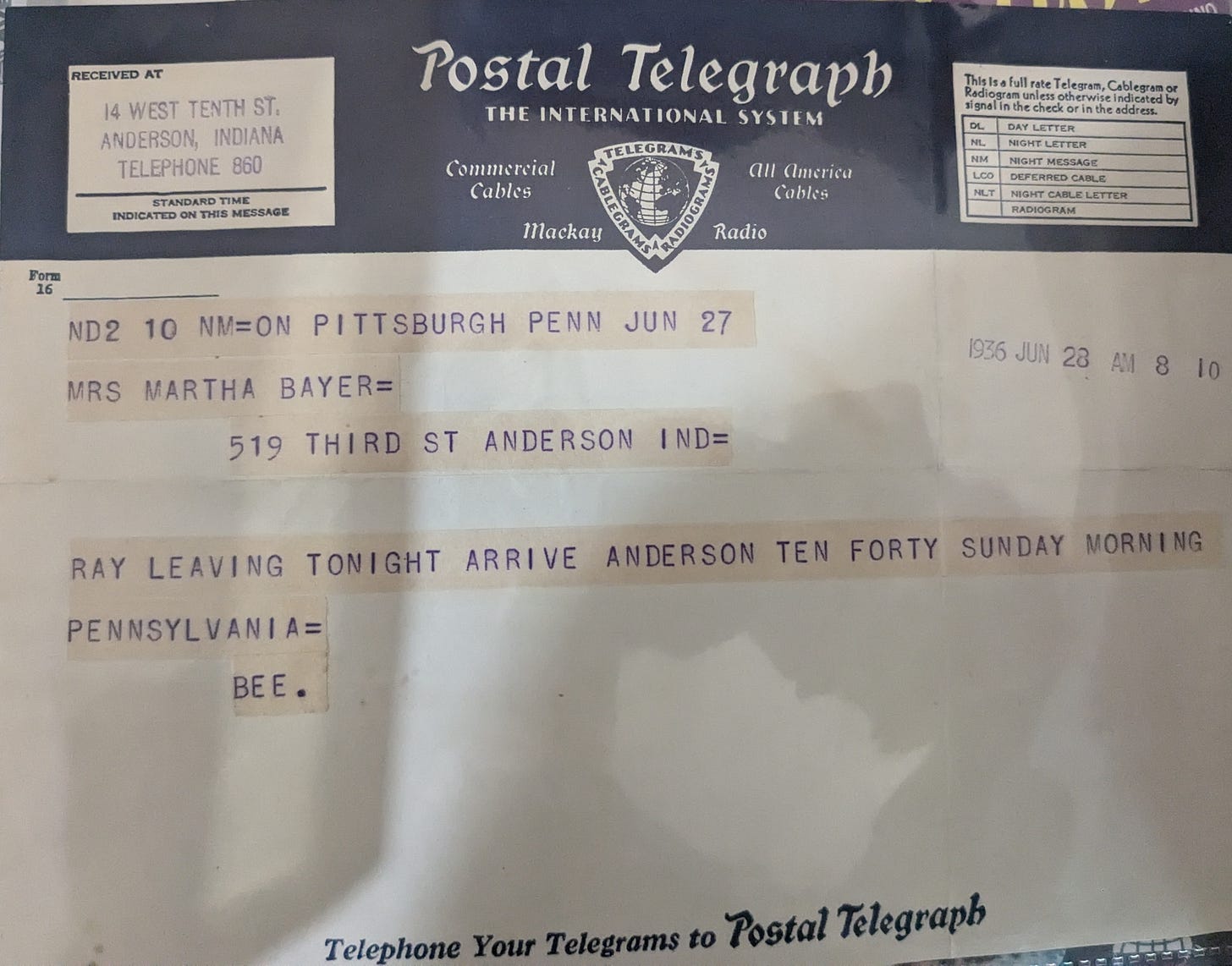

In the back of the store, I opened a little drawer to find a veritable trove of old documents: bank slips from the 1920s, telegrams from the 1930s. For reasons I can hardly explain, I found these little bites of history—the telegrams in particular—quite moving.

I guess what I mean to say is that this telegram is proof that 1936 was a real year, that there were real people there, experiencing real things. Love, loss, annoyance and pleasure. My grasp of the past is so thoroughly mediated by history books and TV shows; it's easy to forget that for billions of people, 1936 was just a year in their life. A point in their experience of time. This telegram is proof that there was a person named Ray, leaving someone named Martha Bayer, due to arrive in Pennsylvania the next day. Even now, it takes my breath away. Does that make sense?

The French philosopher Henri Bergson argued that “spatialized time”—the time of clocks, the time of science, the time of carefully demarcated intervals—does not reflect our actual experience of time. Instead our experience of time is subjective, qualitative. Think of the way an hour feels when it’s spent with friends, and the way an hour feels when it’s spent at the dentist’s office.

For Bergson, time is a constant, indivisible flow, something he called duration, or durée, and it is indelibly tied to consciousness and memory. The past is not dead, on Bergson’s view, nor is it stuck in the “past.” Our memories are stored in our consciousness, and when we access them we also actualize them, bringing them into our experience of the present.

As humans we have a tendency to subjugate the past in favor of the present. Of course we bury the bad stuff, the trauma. But we minimize the good memories as well, whether or not we mean too. We try not to dwell too much on our good experiences; doing so could get in the way of developing and experiencing new ones. We are taught to avoid reverie. We are taught that our memories are epistemically questionable; they might not even be accurate. Bergson argues instead that memories play a crucial role in our construction of the present, indeed in our construction and experience of reality.

I cannot access the memories that surrounded the sending of this telegram. And its brevity and abstracted detail makes it impossible to contextualize in an accurate, meaningful way. I can only wonder about the lives hidden beneath the words. But it reminds me that those lives exist, that Ray and Martha were both embodied, conscious beings with personalized access to Bergson’s mystical realm of “pure memory.”

And the songs of Bill Fox? These old songs, delivered to us as if they were new? These have heft, substance, detail. When Fox sings about the “chains of love” put on him, he cracks open a window into his world of memory and meaning. It is not “bad” that these songs are old. In sharing them with me he has actualized the past, brought these memories into the present. Crucially, these are not re-recorded tracks. These are pure memories, imminence and vitality fully intact. And they are so wonderfully rendered—so detailed in their emotions, in their polemic.

There is a raw, transportive essence to the music that Bill Fox releases, whenever and however he chooses to release it. I hope that continues to write and record songs, and I hope that he gives his small but obsessive audience the opportunity to hear them. He is a cult hero to me and at least a few thousand others. Most of all I hope that his restless soul is able to find some happiness and peace in the light of his immense artistic accomplishments.

![Bill Fox – Transit Byzantium – CD (Album), 1998 [r2176313] | Discogs Bill Fox – Transit Byzantium – CD (Album), 1998 [r2176313] | Discogs](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!iKg_!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3300c624-c6eb-40b0-8d9b-e0864aaf2346_600x600.jpeg)