“In a Razor Town” is the standout track on Isbell’s 2007 album Sirens of The Ditch, the solo project he released only 4 months after leaving the Drive-By Truckers in the midst of a nasty years-long bout with severe alcoholism. The breakup was kinder than most, as DBT lead singer Patterson Hood contributed production to the album and remained close with Isbell. More tricky was Isbell’s relationship with then-DBT bassist Shonna Tucker, to whom he was married - and soon to be divorced. Tucker is also credited for playing on this album, oddly enough.

Although the exact details and dates of Tucker and Isbell’s breakup aren’t clear to me, they also don’t interest me. What matters is that you know “In a Razor Town” was written during a transitional phase of Jason Isbell’s life, as he moved on from a band and a marriage.

As usual, I will mostly elide the formal musical analysis here, because I'm not a trained musician. But this is one of Isbell’s finest musical creations, softer-edged and more winsome than the Southern bar rock he generally played in this era. “In a Razor Town” is elegiac, and its melody has a sort of looping quality to it, a feeling of inevitable return.

Over the last few months I have been hypnotized by this song. Listening to it over and over again, trying to grasp its slippery meanings. Like many of Isbell’s best songs, the lyrics center around a small town. But unlike the classic “Speed Trap Town,” this song isn’t really about a place. What’s more, it lacks a chronological narrative arc. In fact, “In a Razor Town” strikes me as one of the most lyrically ambiguous songs Isbell has ever written, as he works in a referential mode more commonly used by writers like Townes Van Zandt or Bob Dylan. But the song is not inscrutable, and responds generously to careful analysis.

In a razor town you take whoever

You think you can keep around

There's an echoed sound

That permeates the sidewalk

Where she shuffles 'round

Isbell is a master of economy and this song is no exception. The “razor town” in question likely refers to a dying city that uses to have a razor factory, which gives the song a Springsteen flair for the nostalgic. But the “razor town” here isn’t really the focus, instead a thematic template. The only description we get is buried in the suggestion that in a place like this, you take whatever - whoever - you can hold onto.

Here Isbell paints his first image: a woman, shuffling around the sidewalk. We will come back to her, but notice the economic vitality with which Isbell describes the sound of her walking down the block. It’s an echoed sound, one that permeates the sidewalk. Echoes are just right for a place like this, of course. Not even sounds themselves, just memories of sounds.

It's a big machine

It used to be the avenue of changing dreams

And she's a lonely thing, sweeping up the glitter

While she pulls the strings

“Big Machine” is clear enough here, as Isbell references his old band, or the music industry in general. And while this world, this experience of being in a famous band, used to be thrilling - it sure isn't anymore. The glitter is on the ground, being swept up by a lonely woman while she pulls the strings. This is an evocative lyric, and a big hint that Isbell is writing about his ex-wife here, a bass player in a rock band.

Isbell never pulls his punches when writing about others, and this song is no different. If I’m right these lyrics symbolically depict his ex-wife as a depressed vagrant who stumbles around the streets of a burnt-out city and sweeps up trash. More charitably, you could say that he’s using dramatic visual language to depict a woman at the end of the line in her marriage, as both her romantic and musical worlds collapse.

Take a long last look

Before she turns to stone

And what the last man took

And what was long, long gone

Up until this verse, the song’s perspective has been ambiguous, a sort of third-party omniscient. But here something has changed, or come into view. The words make it clear that the song is sung from the perspective of a friend giving relationship advice. If I was to hazard a guess (and I shouldn't), it's from the perspective of one of Isbell’s friends and ex-bandmates from DBT.

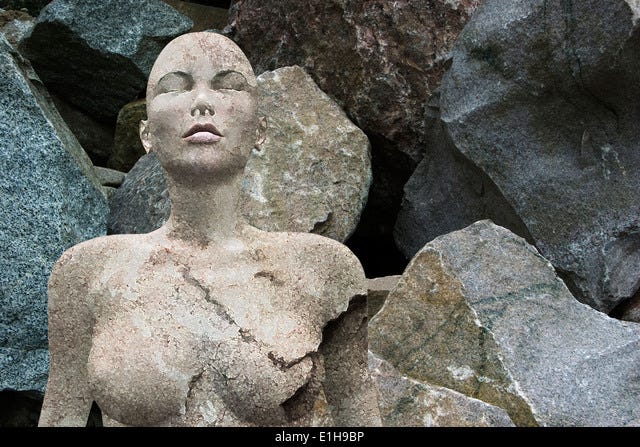

This is also where the songs starts to gather its edge and the lyrics turn a little cruel. We are given reference to what the last man “took,” and what was “long, long gone.” The woman here is positioned as a husk of herself - robbed of her spark - literally turned from flesh into stone. This language occupies a somewhat common male perspective in country songwriting, one that distances itself from the women it supposedly desires by positioning them as beautiful, indecipherable creatures who are here to be hurt or permanently damaged by their encounters with men.

The way it used to be

I wasn't there to see it working properly

And now it seems to me

That both of you are suffering

This writing is so good it makes me laugh - there’s no one who writes quite like Jason Isbell. Just five words, sang in a hopeful tone - “The way it used to be,” conjuring a hallowed era of monogamous calm - are used as a pivot point for the crushing next three lines, as the narrator says he never saw it when it was good, and things seem pretty well fucked up now.

You know I've heard her say

That you're the only reason she's alive today

And I just turned away

Thinking maybe she was right

The narrator says that the woman in question told him she needed Isbell in her life, and so he chose inaction when he knew something wrong. Implicitly he apologizes for not seeing it soon enough, for not stepping in to tell them to break up sooner.

So, say your last goodbye

Make it short and sweet

There ain't no way for you to fly

With her hanging on your feet

Let her go out if she wants to

And if she don't, go out yourself

Don't take sorry for an answer

Unless you really want what's left

These are mean, cutting lyrics. Isbell wrote and sang a song in which his friend tells him to break up with his wife - and in doing so, Isbell describes his wife as a literal deadweight, someone “hanging on your feet.” The use of the second person, the departure from first-person POV, doesn’t change the content.

But as always with him, the nastiness is mixed with a remarkably grown-up sense of humanity, and how people work. Because the narrator also tells Isbell to allow his woman to “go out” if she feels like it. This feels deliciously accurate as to the practical advice you might get from your rockstar buddy - let your wife cheat on you, and if she doesn’t, then you might have to do it yourself. It’s this kind of perfectly-chosen scene detail that grounds a song like this, turning what could be seen as cruel into brutal honesty.

'Cause in a razor town

The only thing that matters

Tends to bring you down

And there's no way around

But maybe you can barrel through

'Cause a razor ain't no good for you

We end with the wistful chorus, the relationship-as-town metaphor brought back to the surface with one more transmutation as we are told that a razor ain’t no good for you (this weak and somewhat rote play on words is an outlier for Isbell).

Although singer-songwriters are inherent egoists, the best of them pair navel-gazing with an innate ability for empathic insight, the ability to understand the feelings of others. This is one of Jason Isbell’s greatest strengths. Rarely will you hear a breakup song written from the perspective of a third-party friend telling the songwriter himself that it’s time to leave his wife. Isbell displays a prodigal empathy for the emotional experience of this friend, conjuring all the sad, apologetic and even didactic feelings that surround the delivery of breakup advice.

Simultaneous to this, however, Isbell evinces a sort of songwriter-autism in his approach to the woman, his theoretical romantic counterpart in the story. It is as if he sees no possible way to have insight into her experience. She is merely a figure to comment upon from afar, to be apologetic about, to witness literally turning to stone. She is an object about which one has feelings, not a subject with interiority and agency of her own. She hangs onto the feet of our heroic rockstar Jason Isbell and keeps him from flying. She must be set free, allowed to leave. And if she won’t leave, she must be abandoned. I’m not calling anyone a misogynist, but I’d be hard-pressed to say the song is not that.

While I see this as a valid critique of the song…I also think the song is perfect. To me these ideas are not contradictory. “In a Razor Town” depicts a thorny emotional scenario with bracing clarity. It is specific to a real-life situation, but it also feels descriptive of a universal human condition, the tendency we all have to end up in places - and with people - we shouldn’t. It smacks of a dead-eyed nostalgia for a past we can’t quite place. I don’t think I will ever lose my taste for it.

P.S.

Other writers have connected this song - take a long, last look, before she turns to stone - to the Greek myth of Orpheus, who tried to escape the Underworld with his lover Eurydice, but ultimately failed. At the end of the journey he ignored warnings and turned to look at her, so Hades swept Eurydice back into the Underworld.

But Eurydice is grabbed by Hades; she doesn’t turn to stone. Medusa is a mythical woman so horrifying that she turns men to stone. And the looking taboo in mythology pops up elsewhere - Lot’s wife turns into a pillar of salt when she looks back at Sodom and Gomorrah. None of these, really have anything to do with this song, at least not on the face of things.

My instinct is that Isbell didn’t think too deeply about which myths he was referencing, and instead was focused on the mythical/biblical weight of the words he wrote in the aforementioned line. That weight is real, adding a spiritual subtext that works despite its lack of meaningful reference to any specific mythological or biblical story.

Glad to see you are back, I was starting to worry. I see you have scraped the internet for stuff on this, I agree, I don't think the whole Orpheus thing holds water, it is not Isbell's style. His references tend to be religious, or other writers, not mythology. I might quibble about the origin of razor, I can see that as a drug reference to cocaine, as much as anything. Its interesting how sobriety and perhaps switching to vaping has improved his voice.

Nice exegesis