Songs You Write Before You Die: David Berman

"That's Just The Way That I Feel," "Nights That Won't Happen," and the wisdom therein

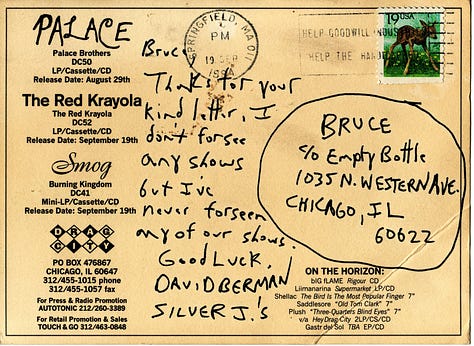

David Berman first achieved cult notoriety in the mid-90s, as the mastermind of the Silver Jews, the band he started in 1989 with Stephen Malkmus (of Pavement). Over the next nineteen years, Berman cycled different figures through the Silver Jews, released a handful of classics, tried to kill himself, reconnected to his Judaism, got married, and abused a litany of hard drugs.

After disbanding the Silver Jews in 2008, Berman effectively disappeared from the public eye for ten years. When he arrived back on the scene in 2019, he had a new band, the Purple Mountains, composed of Berman and the members of a folk-rock outfit called The Woods. As always, Berman’s new band was a one-man showcase for his songwriting, with the lyrics front and center. He sang dense, witty, and punishingly dark songs over upbeat indie rock with country or Americana inflections.

Although Berman arose out of the 90s indie-rock primordial soup, and thus shares some sonic heritage with Pavement (obviously), Modest Mouse, and Yo La Tengo, I think his songwriting hews closer to the “bad” singer bards of the 20th century, specifically Townes Van Zandt and Leonard Cohen.

The self-titled album Purple Mountains was released on July 12th, 2019. On August 7th, 2019, David Berman killed himself.

In the coming months, I will be writing more about David Berman the songwriter and David Berman the Jew. For now, I will take a narrower focus, and write about two songs that scan today as painful exordia to the end of his life. First, “Nights That Won’t Happen:”

Purple Mountains features Berman in a focused mode as a songwriter. “Nights That Won’t Happen” takes the form of a concentrated philosophical statement on mortality and the afterlife.

The dead know what they're doing when they leave this world behind

When the here and the hereafter momentarily align

See the need to speed into the lead suddenly declined

The dead know what they're doing when they leave this world behindAnd as much as we might like to seize the reel and hit rewind

Or quicken our pursuit of what we're guaranteed to find

When the dying's finally done and the suffering subsides

All the suffering gets done by the ones we leave behind

All the suffering gets done by the ones we leave behind

Berman’s directness works to great effect on “Nights That Won’t Happen,” as he delivers a straightforward message: the dead do not suffer. Interestingly, there is a line here that scans as anti-suicidal, when Berman describes the (implicitly foolish) desire to quicken our pursuit of what we’re guaranteed to find. We’re all going to die anyways, so what’s the rush?

My read on the song’s third verse, however, leans the other way.

Ghosts are just old houses dreaming people in the night

Have no doubt about it, hon, the dead will do alright

Go contemplate the evidence and I guarantee you'll find

The dead know what they're doing when they leave this world behind

We start with a wonderful bit of mystical dualism. Ghosts are not ghosts as we traditionally understand them. Berman poses them as soul-boxes, stripped of their content, dreaming of the souls they used to hold within.

Given that Berman had already survived one suicide attempt, the rest of the verse scans as directly suicidal. The inclusion of “hon,” which romanticizes (or at least familiarizes) the subject/listener, makes it all the more crushing. Berman is telling the listener that he/she should find some peace in his eventual death. After all, he will have known exactly what he was doing.

Well, I don't like talkin' to myself

But someone's gotta say it, hell

I mean, things have not been going well

This time I think I finally fucked myself

You see, the life I live is sickening

I spent a decade playing chicken with oblivion

Day to day, I'm neck and neck with giving in

I'm the same old wreck I've always been

Ever the humorist, “That’s Just The Way That I Feel”—the album’s opener—is one of Berman’s flat-out funniest songs. But you take a peek beneath the hood, and things quickly turn pitch-black. This is a lifelong addict, singing about his tendency to play “chicken with oblivion.” And day to day, he’s “neck and neck” with giving in.

I met failure in Australia

I fell ill in Illinois

I nearly lost my genitalia

To an anthill in Des Moines

I was so far gone in Fargo

South Dakota got annoyed

That's the shit I'm talkin' 'bout

When I talk to you about

Ceaseless feasts of schadenfreude

The aforementioned TVZ connection comes through loud and clear in this verse. Listen to “Big Country Blues,” the anti-“Ramblin’ Man,” where Townes mourns the displaced nature of a life on the road.

Spent a lonesome month in Maine and a year in Louisian’

Packed my bags and hit the Westward Trail

Rambled down through Texas 'til I came to El Paso

Spent a week in a stinkin' Juarez jail

The difference here is tonal. Where Townes struck his usual pose of addict nihilism (or stoicism), Berman was a metacognitive goofball. He held himself at arm’s length: close enough for examination, but with enough distance to poke fun. At the core of each song, I think, is the same idea. To borrow from a dumb self-help book I’ll never read: Wherever you go, there you are.

And a setback can be a setup

For a comeback if you don't let up

But this kind of hurtin' won't heal…

There is a dizzying logic to this lead-in stanza, but you have to look closely to understand what he’s saying. If you aren’t careful, if you don’t watch out, your setback can become a setup for a comeback. Here we need to take a step back, and contextualize the stanza in Berman’s life. A former (albeit reluctant) rockstar, with an adoring fanbase, has spent the last decade hiding from the spotlight. His wife leaves him, and maybe he relapses—or doesn’t, but knows a relapse is possible.

He’s hitting rock bottom, or damn close. In this light, we can translate the stanza from Bermanese to English: If you aren’t careful, your “rock bottom” breakup/relapse will eventually lead to you becoming an indie rockstar again.

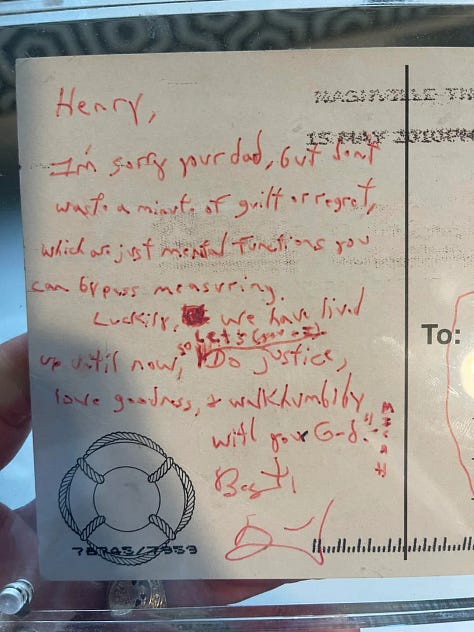

Isn’t a comeback a good thing? For an infamously depressive recluse…maybe not. Maybe the comeback was a bad idea. Maybe he didn’t wish to be famous; maybe he didn’t wish to be perceived. However tempting this idea, I think it’s too simplistic. If you read about Berman, listen to those who knew him best, he was a deeply personable and kind friend in private. He loved hearing from fans, and wrote countless letters to well-wishers and advice-seekers. And there was clearly an intense, unending desire to create and share his art. A desire to live, to make, to experience.

And the end of all wanting

Is all I've been wanting

The end of all wanting

Is all I've been wanting

The end of all wanting

Is all I've been wanting

And that's just the way that I feel

The song’s chorus, which repeats at the close, is almost too much to bear in context. Could he have said it any plainer? At the time of writing this song, at least, he wanted to die. And die he did, checking out of this world by his own hand, having spent the same amount of time—52 years—on Earth as Townes Van Zandt.

I know that this type of analysis is gloomy, bordering on macabre. The tendency to hallow a dead artist’s final songs, to treat David Berman’s final songs as suicide notes, doesn’t always come from a good place. But in the case of the elliptically brilliant and ever-mordant Berman, I find it inescapable. I think it’s in the songs, in the lines, in the words.

In an ideal world, David Berman would have found a great therapist, or rabbi, or a new girlfriend, or found some peace in a regimen of Lexapro and melatonin. It is truly horrible and tragic that he felt a need to—in his own words—quicken his pursuit of what we’re guaranteed to find. But a half-decade later, as I pick through his lyrics to extract wisdom if not comfort, I think I have found some of both in “Nights That Won’t Happen.”

Have no doubt about it, hon, the dead will do alright

Go contemplate the evidence and I guarantee you'll find

The dead know what they're doing when they leave this world behind

Dani,

This was a beautifully written and deeply thoughtful piece. You captured the complexity of David Berman’s life and artistry with such care, balancing admiration for his work with the painful reality of his struggles. Your analysis of his lyrics, especially the way you frame “Nights That Won’t Happen” and “That’s Just The Way That I Feel” - felt like peeling back layers of meaning, revealing both his resignation and his dark humor.

I appreciate the way you place Berman within the lineage of singer-songwriters like Townes Van Zandt and Leonard Cohen while also highlighting what made him singular. His ability to hold sorrow and wit in the same breath, to write lyrics that felt both intimate and universal, is something few artists can achieve.

It is heartbreaking to read between the lines of his final songs, yet your piece makes it clear that while he may have left this world, his words, and the complicated truths they carry, endure.

Thank you for this, and I look forward to your next piece.