The Weirdest Song that Sufjan Stevens Ever Wrote

Emotionally researching "John Wayne Gacy Jr.," one of Sufjan Stevens' most challenging works

understanding sufjan

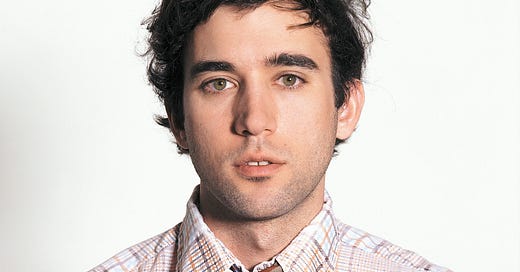

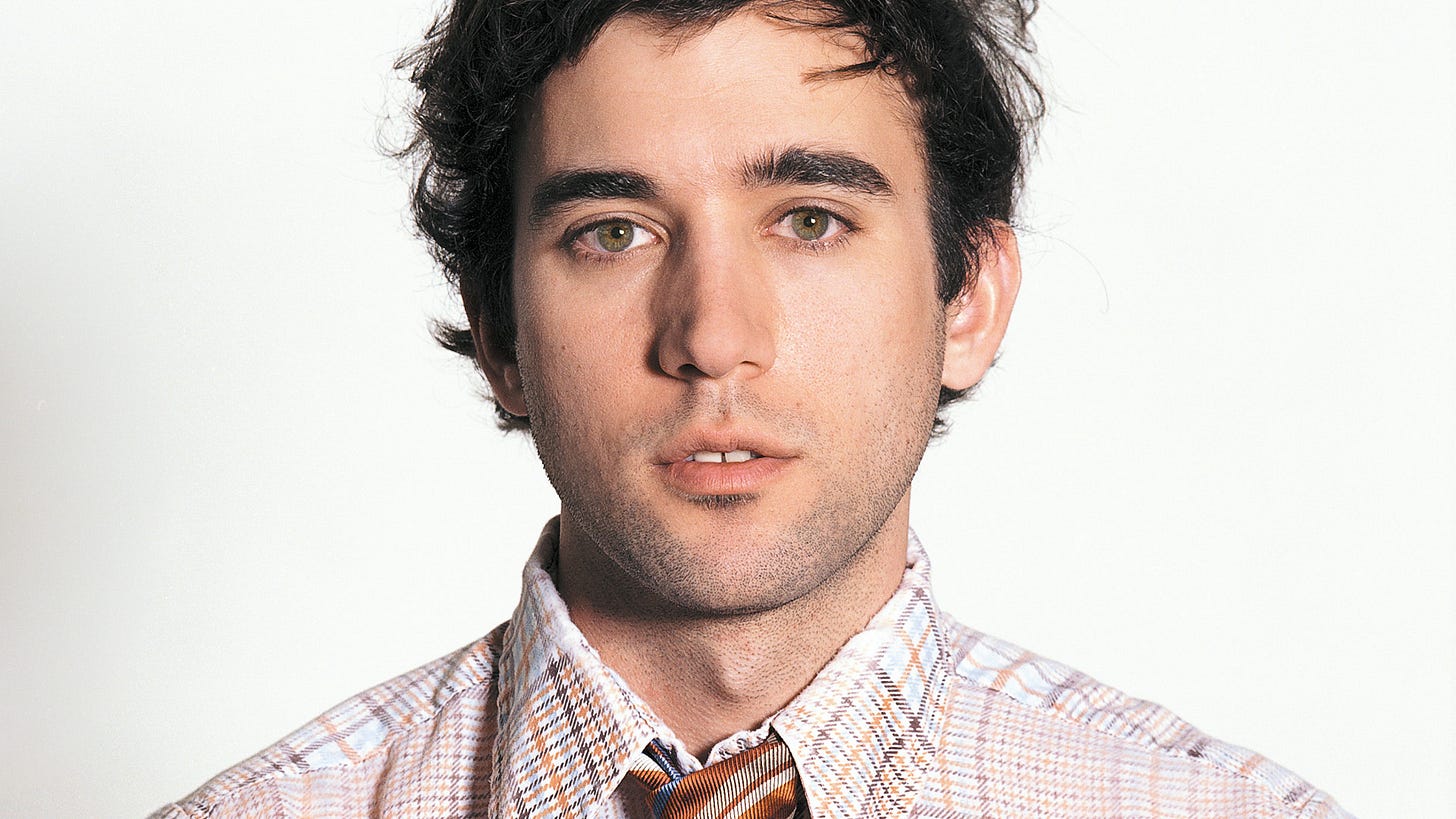

The word “enigmatic” is defined as difficult to understand, which means that when I call the folk singer-songwriter Sufjan Stevens enigmatic, I am basically saying that I don’t know how to describe him. I could try some other adjectives, like: genius, gay, prolific, Christian. These are all accurate, but they don’t say enough, because Sufjan Stevens really is enigmatic.

This is a man who once announced his intention to make one album for each state in the Union, recorded Michigan (2003) and Illinois (2005)—both widely regarded as classics—and promptly gave up on the idea with 48 albums to go. This is an artist whose 2020 album, Ascension, was heavily electronic—primarily due to a shitty landlord situation in Brooklyn that led to Sufjan’s favorite guitar being in storage. This is a guy who recently said that 2015’s Carrie and Lowell—the rare perfect album, a stunning accomplishment that received universal praise—was a “failure,” and referred to his songwriting on the project as a “miscarriage of bad intentions.”

Sufjan has generally refused to make political statements; he rarely gives interviews. He pops up occasionally as a credited producer on some genuinely bad music, made by artists no one has ever heard of. Though his lyrics have carried oblique allusions to his sexuality for decades, it was only very recently that he explicitly “came out” in a poignant 2023 Instagram post mourning the death of his late partner.

the song i’m writing about today

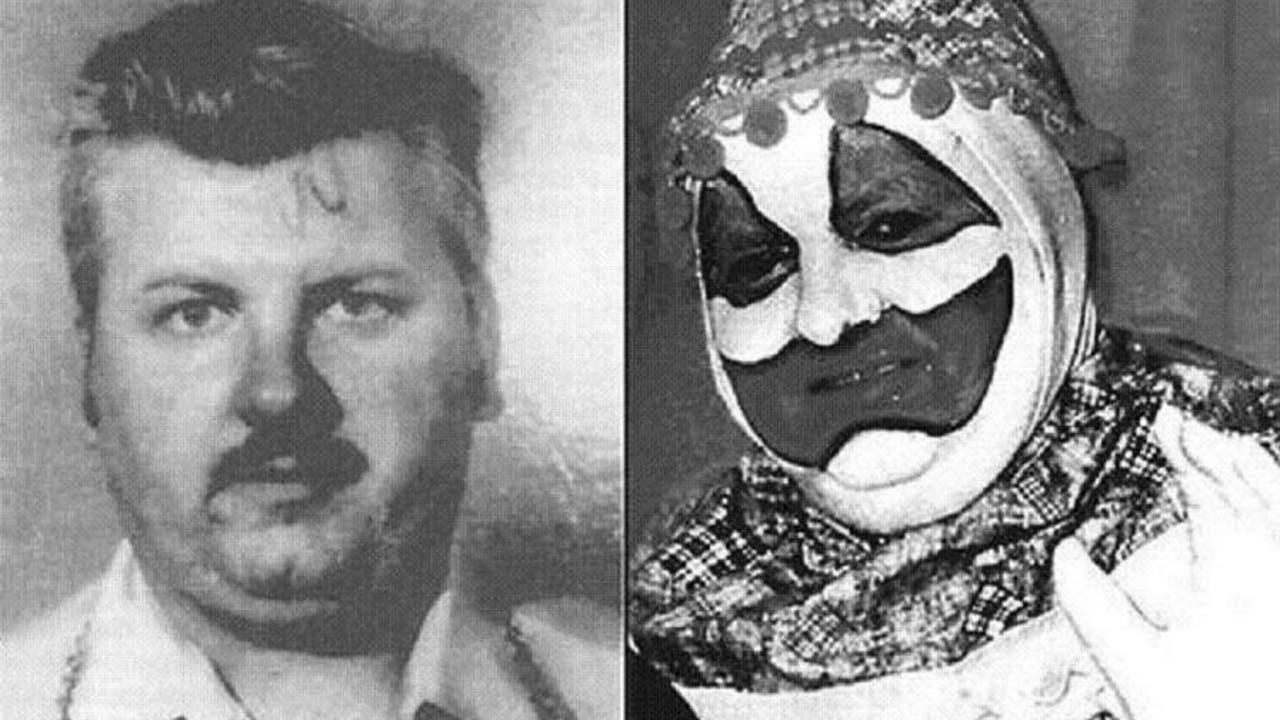

This enigmatic quality permeates Sufjan’s discography, particularly in some of his earlier, research-heavy songwriting, exemplified by “John Wayne Gacy, Jr.,” a bizarre and profound song about the infamous serial-killing clown. It’s a gorgeous bit of sparse folk music, with whispery vocals over a simple, fingerpicked chord progression. Sonically, it lands somewhere in between Elliott Smith and Nick Drake.

The premise of this song, it must be said, verges on poor taste. John Wayne Gacy, Jr. was a serial killer in an outlying Chicago suburb who sexually abused and then murdered at least 33 young men and boys; it is possible there are more victims, as-yet unidentified. He buried most of the bodies in the crawl space under his house, and threw some into the river. Yet Sufjan starts the song with an unsettlingly empathetic glimpse into the childhood of the serial killer.

His father was a drinker

And his mother cried in bed

Folding John Wayne's t-shirts

When the swingset hit his head

The neighbors, they adored him

For his humor and his conversation

Here, Sufjan evinces a sort of entry-level criminal psychological explanation for how someone like John Wayne Gacy, Jr. becomes a serial killer. An alcoholic dad, a fucked-up mom, and a childhood brain injury. He also emphasizes the killer’s well-documented charisma. There is a focus on economy in these lyrics; in just a few lines, Sufjan has conjured an unnerving familiarity with the song’s subject.

Look underneath the house there

Find the few living things, rotting fast, in their sleep

Oh, the dead

Twenty-seven people

Even more, they were boys

With their cars, summer jobs

Oh my God

Are you one of them?

This is a clever verse, structured to make the listener confront the bracing reality of Gacy’s dead victims. It starts in a place of naivete, as the listener is told to look in the crawl space, find the “living things, rotting fast, in their sleep…” This is how a child might understand the bodies. Next they are referred to as “the dead,” and then they become “twenty-seven people,” and then it’s like Sufjan himself begins to recognize their specific humanity with the breathless lines: “Even more, they were boys, with their cars, summer jobs,” and this painful realization impacts his vocal approach, forcing him into a stunning falsetto as he moans “Oh my God…”

The effect is that of Sufjan himself, alongside the listener, beginning to understand the immense weight of John Wayne Gacy Jr.’s crimes. The verse ends in ambiguity with the hushed, curious: “Are you one of them?” He is singing to himself and to his audience, asking them if they—like him—empathize with the victims; asking if they—like him—see something of themselves in the dead boys.

He dressed up like a clown for them

With his face paint white and red

And on his best behavior

In a dark room on the bed

He kissed them all

He'd kill ten thousand people

With a sleight of his hand

Running far, running fast to the dead

He took off all their clothes for them

He put a cloth on their lips

Quiet hands, quiet kiss on the mouth

It bears reiterating that this song shouldn’t actually work. It is incredibly disturbing; in this verse, Stevens describes the prelude to the murders. These are abusive acts, but he makes them sound delicate, softly ritualistic. The stripping of the murder victims becomes: “He took off all their clothes for them.” The use of chloroform to knock out the murder victims becomes “He put a cloth on their lips.”

But if you listen to the song with an open mind, I suspect that 'you’ll find it does more than work. It is so beautiful to listen to, so tenderly written and performed, that the content slips right past you. And the song’s closing lyrics reveal that it’s not about John Wayne Gacy, Jr. at all.

And in my best behavior

I am really just like him

Look beneath the floorboards

For the secrets I have hid

Just like a movie’s closing shot or a book’s final pages, the last words of a great song can reveal its true meaning. In the case of Sufjan Steven’s “John Wayne Gacy, Jr.,” the subject is Sufjan Stevens. The metaphorical imagery is vivid and direct. Dead bodies beneath the floorboards evoke secrets kept for too long, sins buried deep. And in the case of Sufjan Stevens, a man who spent decades in the spotlight without explicitly revealing his sexuality, the resonance is clear.

I want to be clear that this song is not just about “being gay,” or being closeted. That would be too simple for a writer of Stevens’ depth. But it’s not not about those things, either. This is a celebrity who spent over 20 years in the shadows, restraining from public indication of his sexual or romantic life. I think this song might be about the guilt that often comes with casual sex, the internalized sorrow one feels post-seduction, post-physicality, when your partner has been discarded. It might be about boyfriends past, even serious boyfriends, men whose importance to Sufjan was never publicized. I say might because this song, much like Sufjan, really is enigmatic, really does resist unsubtle analysis.

In “John Wayne Gacy, Jr.” Sufjan identifies with a serial killer not to humanize the serial killer, but to pathologize himself. It is a searching and wistful interrogation of his psychological makeup, a bracing awareness of interior darkness. It makes me imagine its writer standing in front of a mirror, picking at his pores. It’s also one of the prettiest songs ever made, and that dualism—the way his art holds space for deeply oppositional qualities—is key to the herculean task of describing Sufjan Stevens.

Really thoughtful piece!